The Poetics of Letters

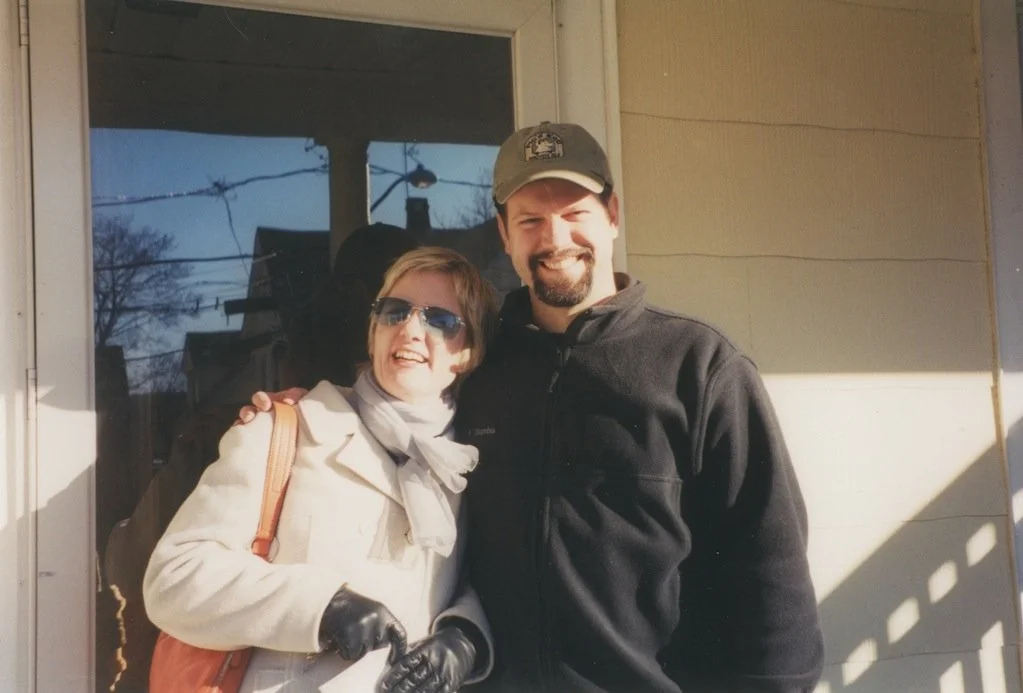

How stunning to realize, as I begin to think about the poetic company, that Daniel Bouchard and I have been writing to each other for twenty years! When we began our correspondence, I was living in Providence, he in Boston. Lee Ann Brown, whom he had looked up following a tip from Lyn Hejinian, introduced us. A little while later we met for a second time at an after-poetry-reading party at Peter (Gizzi) and Liz’s (Willis). Because they lived across the street from Steve and me, it was easy to invite Dan up to our apartment and give him a bunch of Impercipients. I had put together six issues to date; Dan’s work would appear in the seventh.

The oldest letter I can find from Dan is dated May 15, 1995. “It’s been nearly a month since we spoke on the phone,” he says, “I wanted (finally) to write something to let you know I was serious in suggesting a correspondence.” This was the pre-social media equivalent of a “friend request.” That first letter also mentions that “a year ago to the week” he had finished his MA at Temple and left Philadelphia. I too had finished a graduate degree the previous year, my MFA from Brown. We were in that precarious post-graduate-school phase, trying to figure out how to be poets and continue to participate in a dialogue about poetry.

Starting a correspondence with Dan was propitious, for if his letters to me were various in material and method—typed, handwritten, on anything from fine stationery to lined notebook paper—they were consistent in their record of Dan’s passion for reading. In that first letter he wrote that, due to moving apartments, his “Tenuous (indeed, strenuous!) reading habits” had been “shattered.” Despite which fact he includes a lengthy discussion of Oppen’s work and mentions reading Silliman’s New Sentence, in addition to autobiographies of “Big” Bill Haywood and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. These last choices attest to Dan’s interest in labor history. This interest led him to interrogate something he’d just heard about in reference to writers like Philip Levine called “work poetry”:

I was in Philadelphia last weekend and had the chance to see many students from the Temple program. Two talked with me about what they called “work poetry . . . [t]he inflection of their voice[s] when saying “work poetry” made it sound like a genre, if not a movement, and I was hesitant to suggest that maybe it’s poetry with ‘work’ as a subject matter.

I love the clarity of this insight. It is the sort of “emperor’s new clothes” observation that Dan excels at. I can’t say how many times I’ve been agonizing over some poetry-world kerfuffle only to have Dan cut right through the nonsense. In my June 28, 1995 letter I respond to the issue of “work and poetry”: “I still use the word ‘work’ for poetry,” I write, “and yet a while back I vowed not to.” This vow lead to my writing of a failed essay titled “Why Poetry Is Not Working.”

I had forgotten all about this essay until I came across a letter from Dan responding to it. Reading through his old letters I am struck by how consistently I have relied on him as a first reader for much of what I write—especially work I feel nervous about or unsure of. I worried, in that June 1995 letter, that the writing of my memoir might take two more years. It took nine. I have a letter from Dan, dated 2004, that includes a detailed response to a finished draft of The Middle Room.

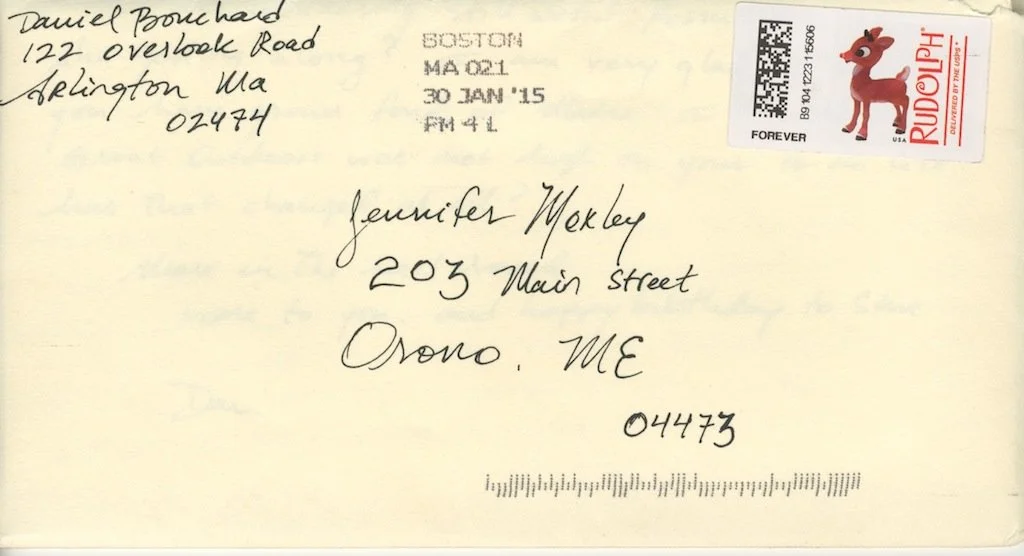

In his most recent letter, postmarked January 30, 2015—from his home in Arlington, MA where he now lives with his wife Kate and daughters Anna and Maggie—I learn that he’s reading a travel book by Norman Douglas called Siren Land from 1911 and Jackson MacLow’s Light Poems, new from Chax Press. As regards my booklist he recommends, fearing it may not be the first time, Gore Vidal’s Lincoln, Burr, and possibly Julian (I think Dan has read everything Vidal wrote). He also responds generously to a draft of something I sent him with my last letter.

Advertisement for Mass Ave Magazine

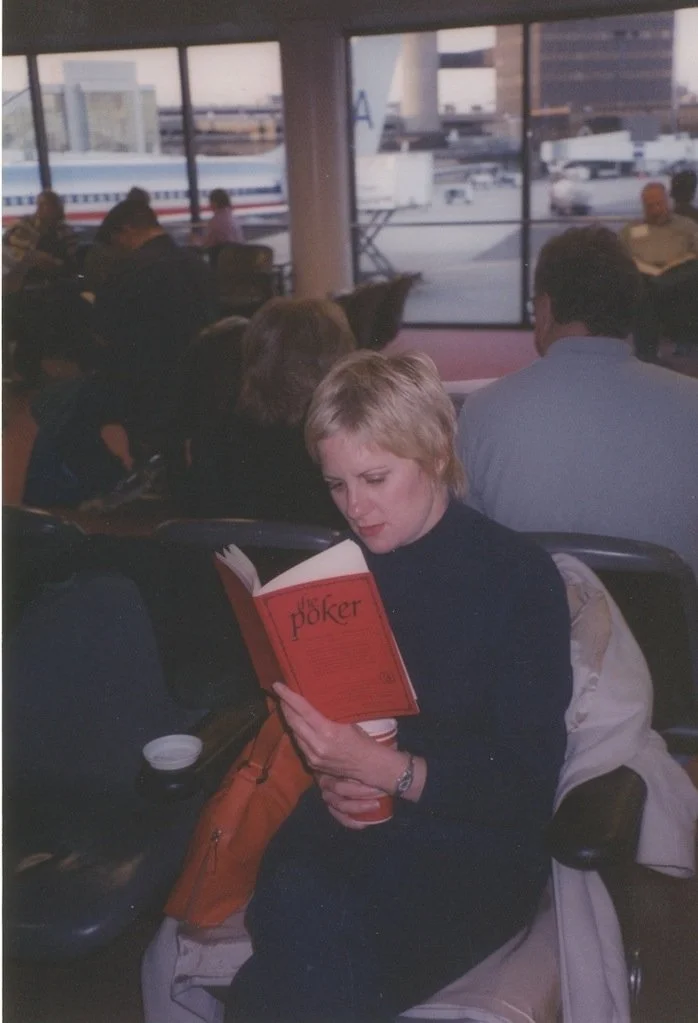

I think I have established that Dan Bouchard reads—widely and variously—but he also, in addition to writing poems and letters, keeps a journal, and has been a founder and editor of two magazines: Mass Ave. (three issues, 1996-97) and ThePoker (nine issues, 2003-09). The first of these, Mass Ave., was invested—as its name signals—in the geographical situatedness of each contributor (names in the TOC are followed by place of residence). An Olsonian gesture, and doubly striking now that we so often find ourselves “friends” with people virtually—sometimes without any sense as to where they live. The cover of the third issue has a black and white cut out of two of the little girls from John Singer Sargeant’s The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit. Looking at them now, I can’t help thinking that when making this design choice, Dan must have been having a premonition of his future fatherhood (Sargeant’s painting has four girls in it, but Dan only put two on the cover, two that bear a striking resemblance to his own Anna and Maggie!).

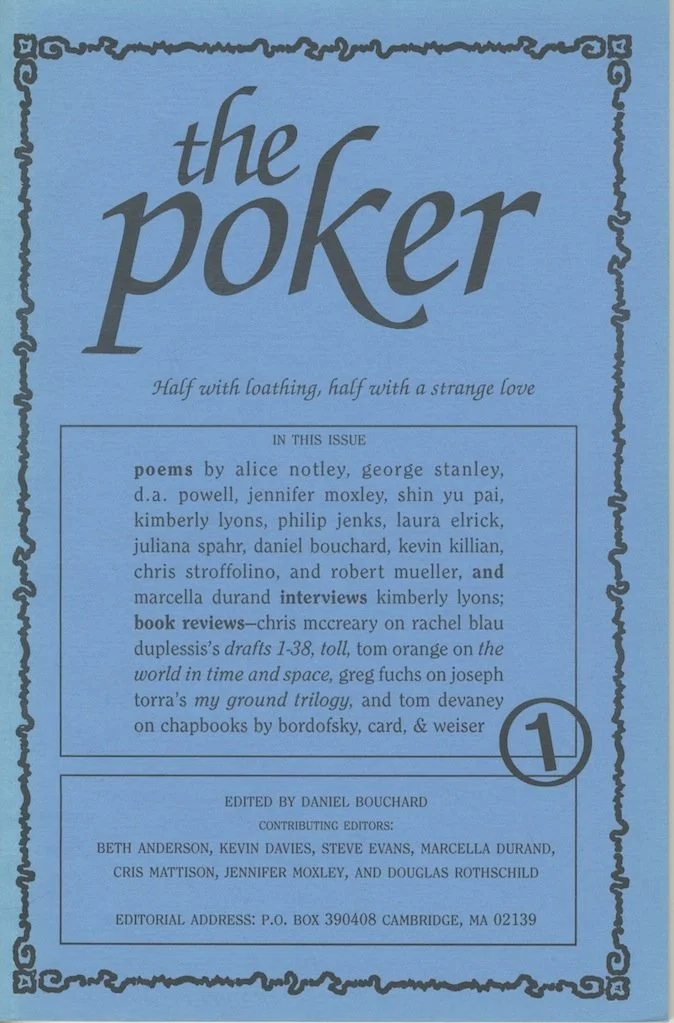

A letter dated March 13, 2002 records the genesis of his second magazine, The Poker. I love this passage, because it so exemplifies the exhilaration of imagining one’s “dream magazine”:

So: I want to start a magazine and this is how I’m going to do it. It’ll be cheap, 8 1/2 x 11 trim photocopied. Copy costs and most of the mailing, I hope, subsidized by you know what. And it will be monthly, which will compensate for its on-the-fly look. But it will be exquisitely typeset. And it will be very exciting. Small: 32 pages I think. Solicited cover art: original, archival photos, parodies, something to flush adrenaline.

Ten months later the premier issue of The Poker was in the world, and though the real thing differed quite a bit from the description above, it was very exciting. The Poker’s epigraph, “Half with loathing, half with a strange love,” came from Richard Eberhardt’s poem “The Groundhog,” in which the poet “pokes” a decaying groundhog with an “angry stick.” Steve and I were contributing editors, as were Beth Anderson, Kevin Davies, Marcella Durand, Chris Mattison, and Douglas Rothschild.

First Issue of The Poker

The writing of this post was put in some jeopardy by The Poker, because when I pulled down my stack of copies to review I felt an overwhelming desire to reread every issue. The Poker is an unparalleled document of a particular moment in a community of poets. Dan managed to get great work out of his contributors. He included poems, interviews (with Alice Notley, Robin Blaser, Kevin Davies, Anselm Berrigan among others), reviews, scholarship and criticism (including Ben Friedlander on 19th century poet Fitz-Greene Halleck, Matt Gagnon on Robin Blaser, and Steve Evans’s Field Notes installments) archival materials (from Williams, Schuyler, Oppen, Spicer and others), debates and critical conversations (for example, Aaron Kunin questions the idea of “reading” posited by Juliana Spahr’s Everybody’s Autonomy in issue 3; in issue 4, Spahr responds), and letters to the editor.

Dan was generous enough to publish my poetics essays “Ancients and Contemporaries” and “Lyric Poetry and the Inassimilable Life”—neither would have made sense in an academic journal.

As I understand it, Dan still has some copies of The Poker in his basement, and given the amount of snow Boston has received this winter, I fear the melt might put those copies at risk. I would encourage any readers who haven’t seen this magazine to write to Dan for copies before spring melt sets in.

Literary correspondences—such as the one Dan and I have shared these past twenty years—can be crucial in the shaping of a poet’s ideas and critical thinking. Or so I argued at the 2006 AWP Annual Conference in Austin. Joshua Clover had invited me to be part of a panel titled, “Where the Poet-Critics Are,” and in my talk I pointed out that some of the most enduring statements we have from poets came from their letters: poets such as Keats, Dickinson, and Rimbaud.

A correspondence continued over many years with the same person allows for the slow development of aesthetic ideas in an environment of trust, trust built via subsequent confessions, the sharing of ideas, and yes, texts. The time and space of the handheld pen on the page (or fingers on the keyboard) directed to one individual, and with the knowledge that what you write cannot be forwarded with the push of a button, is unlike any other space.

I know there is something old fashioned in this view, something old world. It gestures toward a past we cannot recover in the post-digital world, as does the following scene, written by hand in a letter from Dan marked “Blizzard of 2015”: “Our junior housemates . . . soon followed their mama up to the attic . . . and left me in this eerie silence. No cars pass.” Winter turns back the clock, and suddenly my interlocutor finds himself sharing Coleridge’s experience in “Frost At Midnight.”

How glad I am that, through a letter, I was invited to share it as well.