Backyard Carmen

Not long ago, Steve and I were invited to join a taskforce charged with growing the audience for the Metropolitan Live in HD opera broadcasts at the Collins Center for the Arts, UMaine’s largest performing arts venue. We are, sadly, the youngest members of this taskforce by some years. In addition to being primarily drawn from the senior set, the typical audience for the Met Live in HD amounts to about a hundred people, which not only looks scant in an auditorium of 1,500 seats, but has the director threatening to cancel the broadcasts altogether—a worrisome prospect to those of us who regularly attend. The largest audience was 270, for a broadcast of Carmen with Elīna Garanča in 2010. Saturday November first the Met is broadcasting Carmen again, this time with the Georgian mezzo Anita Rachvelishvili. Steve, in hopes of interesting the students taking his course on the Lover’s Discourse, spent some time finding alluring YouTube clips from Carmen, including a wonderful Muppet’s sound-poem version of the Habenera. From his report, few students seemed moved to interrupt nursing Halloween hangovers with initiation into this alien art form. All this Carmen talk reminded of my own history with Georges Bizet’s classic, which was my first exposure to opera, enhanced by a Maria Callas recording given to me by my mother. As I wrote in The Middle Room:

Saturday November first the Met is broadcasting Carmen again, this time with the Georgian mezzo Anita Rachvelishvili. Steve, in hopes of interesting the students taking his course on the Lover’s Discourse, spent some time finding alluring YouTube clips from Carmen, including a wonderful Muppet’s sound-poem version of the Habenera. From his report, few students seemed moved to interrupt nursing Halloween hangovers with initiation into this alien art form. All this Carmen talk reminded of my own history with Georges Bizet’s classic, which was my first exposure to opera, enhanced by a Maria Callas recording given to me by my mother. As I wrote in The Middle Room:

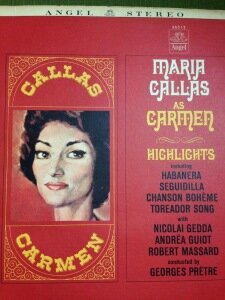

Callas’s was the first operatic voice I had ever heard because Jo had given me a recording of her singing highlights from Carmen when I was ten. I was mad for the music after our fifth-grade class, in the interest of cultural edification, had gone to hear Bizet’s masterwork on an afternoon field trip. When the performance was over we were invited backstage to meet the soprano. Though I don’t remember her name, I remember that she was very beautiful and gave each of us a signed photo of herself wearing a low-cut peasant blouse and holding a rose in her teeth. . . .

The Callas record Jo bought for me, and which I still have to this day, had the dubious honor of serving as soundtrack to a backyard production of Carmen I directed and starred in the following summer. I cast my friend J_________ as Don José, and made her spend my entire castanet dance frozen still in the identical posture of Rodin’s “The Thinker.” Exactly two neighborhood retirees made our lawn-chair audience, and after the rousing finish they offered J_________ and me one chocolate bar each, sweets that they dug from the depths of their purses as if they were precious heirlooms that had been hidden inside them for many years.

That my first “audience” was not only small, “two neighborhood retirees,” but decidedly older and “unhip,” neither perturbed nor dissuaded me from my youthful belief that Carmen was a great work. That it had moved me was enough—it didn’t need to be popular. The irony being, of course, that Carmen was and is “popular,” in the radical sense of that word. Carmen is a gypsy, she is vulgar, public, of the people, on display. She was my first mentor in femme fatale-ism. As one of the opera’s earliest reviewers wrote: “To see her, rocking her hips like a filly on a stud farm in Cordova: quelle vérité, mais quel scandale.” Carmen is, like the girl in Heart’s great song “Kick It Out,” a “tail shakin’ filly.” I couldn’t resist her. And while many people, both young and old, may do just that, “audience”—if we take the long view—has never been Carmen’s issue. One hundred and thirty-nine years after its debut at the Paris Opéra-Comique, people are drawn to the story of this immoral seductress and Bizet’s irresistible music. Why are we made to feel that just because right now, in 2014, Carmen lacks what Facebook has, “a billion users,” its artform is obsolete?Anxiety over audience size is familiar to poets. And while compared to opera, poetry is cheap, and therefore technically more accessible, both are subject to the paradoxical accusation of being both unwanted and exclusionary. Last week, a former student with a new book out emailed me asking for advice on how to get her book reviewed and into “the hands of readers.” Given that my 2012 book There Are Things We Live Among received no reviews, I thought, rather diva-like I’ll admit— given that before Things I’ve been fairly privileged in this regard—“I’ve no idea how to get a book reviewed, or into the hands of readers, if you find a way, let me know!” In my life in poetry, the anonymous construct of “audience” remains an abstraction. It makes me uncomfortable, as uncomfortable as I am made by the suggestion that I must proselytize to keep the things I love alive, whether charming opera broadcasts, or dreary outdated poems.Don José posed as The Thinker recalls that Rodin mentored Rilke. In Ulrich Baer’s Rilke Alphabet, I read about how two participants in a 1907 survey about books that are “indispensable . . . . for [the future of] existence” cite Rilke’s poetry. “[E]ven if it did ‘not find a large audience’ in the present,” Rilke’s will be, they assert, a “major work of the future.” This has certainly come true. Just as Keats cannot be said to have had anything resembling an audience during his lifetime, and yet how many readers since? After all, “A poet needs only one poem, a poem only one reader” (Fragments of a Broken Poetics). But is a reader the same as an audience? Another Fragment: “The idea of audience is a nuisance born of the need for spectacle. Poems haunting the precarious dialectic between existence and extinction do not need it. Their magic is dependent on the private experience of separate individuals.”To have an audience is to be given a hearing. However much I wish to dismiss it, this seems as essential to poetry as to opera. The ears have it. But is this “hearing” also the source of that crushing feeling of isolation I am felled by each time I give a poetry reading? The moment Rosa Alcalá, after reading here in Maine, called “the loneliest moment in poetry”?